By denying women the right to work, you degrade her; you put her under man’s yoke and deliver her over to man’s good pleasure… It is work alone that makes independence possible and without which there is no dignity.

– Paule Mink (1868, cited in Offen, 2000, 138).

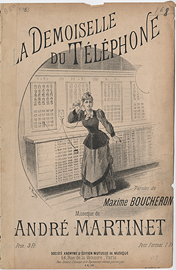

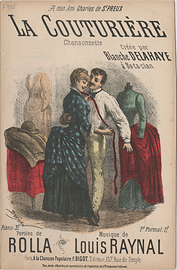

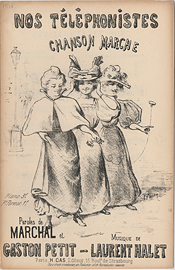

Amid increased industrialization, urbanization, and political change, new employment possibilities for women emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century. Women could become teachers, nurses, bank clerks, cashiers, shop girls, postal workers, and telegraph and telephone operators, to name but a few of the new métiers féminins. In particular, technological developments and commercial growth fostered these new professional opportunities within urban centers. Beginning in the 1860s, newly created telegraph and telephone companies hired women as operators, and in 1892 women started to work for the postal service in the white-collar position of the dame employée. The new Parisian department stores also hired single young woman as shop girls.

Class and marital status influenced women’s participation within the workforce, as Joan Scott and Louise Tilly have emphasized (1975, 1978). Many of these new métiers féminins were adapted for middle-class women who would stop working once married, unlike poorer women who needed to work for the sustenance of their families. In reality, many working-class women continued to be employed in traditional jobs in the textile industry, in agriculture, and in domestic service. New legislation in the 1890s that established a minimum age and restricted work hours, however, arguably improved the situation of female factory worker.

Prominent feminists of the era, such as Paule Mink, celebrated women’s work as an escape from the drudgery of housework. Nevertheless, women’s participation in the workforce was not embraced by everyone. Given France’s alarmingly low birthrate, concerns emerged about women’s work undermining their health and “natural” role as mother. Jules Michelet argued women should not be working outside of the household, and in La Femme he denounced the very term ouvrière (female worker) as “sordid” and “impious” (1860, 22). Jules Simon went so far as to declare that “Woman, having become an ouvrière, is no longer a woman” (1861, vi).