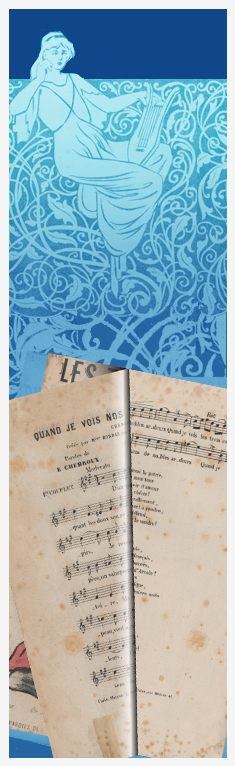

“Women, Work, and Song in Nineteenth-Century France” explores both women’s work and the cultural work about women in the popular song industry, drawing on a selection of pieces from the 19th-Century French Sheet Music Collection at the Marvin Duchow Music Library. The exhibition highlights the varied and evolving roles of women over the course of the century, as producers, singers, and workers. These roles were inextricably linked to social developments, politics, revolutions and armed conflicts, the effects of the industrial revolution, and the expansion of consumer culture. The exhibition pieces reveal the cultural reaction to the changing position of women in society, observed in the songs’ text, music, and cover illustration (which were primarily created by men).

The popular sheet music industry thrived in nineteenth-century France. In 1845, J.-A. Delaire estimated that 250,000 copies of romances were printed annually; by the 1880s, a single café-concert chanson could have a print run of over 100,000. With literally millions of songs in circulation, many forgotten within a few months, it is no wonder that much of the commentary on the sheet music industry has highlighted its ephemerality and its complicity in the development of mass consumer culture. And yet commercial sheet music has extraordinary value for individuals seeking to delve into experiences of daily life during the period. Not only do many songs reflect on and respond to contemporary events, political conflicts, social developments, and cultural concerns, but each piece of music also presents an opportunity to trace a vast and complex network of agents who contributed to its creation, performance, and circulation.

Many of those agents were women. Scholarship on women and the sheet music industry has tended to emphasize their role as consumers or as performers in a domestic setting, typically through the motif of the lady at the piano. Such research importantly highlights the often-overlooked, invisible practices of music making; however, it only hints at the scope of women’s influence, presence, and contributions in the industry. Women were composers and poets. They performed the songs in various settings, from private dwellings (the home) to semi-public venues (salons, private concerts) to the public stage. Women hosted salons, and worked as publishers, engravers, and music-sellers.

Women were also objects of inspiration for the songs themselves, either featured in the text or emblazoned on the sheet music cover. Representations of women in popular song ranged from shopworn clichés of the love-stricken damsel to erotic images of the cocotte. But many songs also engaged with debates about the place of women in society, just as those questions were being brought into the public spotlight by feminists, writers, and politicians.

The exhibition follows a chronological narrative, charting the shift in genres, venues, and the means of dissemination of French song over the course of the century: the salons of the July Monarchy, the café-concerts of the Second Empire, and the music halls and cabarets of the Third Republic. The individual categories explore various aspects of the exhibition’s three themes—Women, Work, and Song. While the themes overlap in many ways, they highlight dissonances between women’s real experiences during the period and the male fantasies about them. “Women” investigates representations of women and perceptions about their role within French society: in other words, women as idea or symbol, and the cultural and musical responses to their changing position in the home and the nation. “Work” takes up the musical illustrations of women in the workforce, focusing on the increasing variety and availability of jobs as a result of the industrial revolution and developments in communication technology. “Song” focuses on women’s contributions to the music industry, through their work behind the scenes and on the stage, as composers, librettists, singers, salonnières, and publishers.

Co-curators: Kathleen Hulley, Ph.D., and Kimberly White, Ph.D.