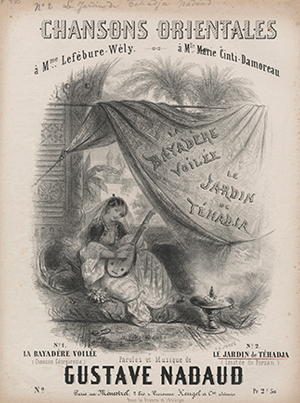

“Le jardin de Téhadjâ.” Chansons orientales

In 1852, President Bonaparte became Napoléon III, Emperor of the French, thus inaugurating the Second Empire, which lasted until France’s defeat during the Franco-Prussian War. It was a period of economic prosperity, political stability, and modernization. France expanded the railways, which by 1855 connected all sectors of the country with a 10,000 km network that radiated from the capital. As prefect of the Seine, Baron Haussmann redrew the map of Paris: he erected wide boulevards and direct roadways, created a larger sewer system, improved street lighting, and established city parks. Paris hosted its first Exposition Universelle in 1855, and then again in each decade until the century’s end (1867, 1878, 1889, and 1900), displaying the nation’s industrial and cultural products, and its colonial exploits from Indochina to Africa.

“Le jardin de Téhadjâ.” Chansons orientales

In 1852, President Bonaparte became Napoléon III, Emperor of the French, thus inaugurating the Second Empire, which lasted until France’s defeat during the Franco-Prussian War. It was a period of economic prosperity, political stability, and modernization. France expanded the railways, which by 1855 connected all sectors of the country with a 10,000 km network that radiated from the capital. As prefect of the Seine, Baron Haussmann redrew the map of Paris: he erected wide boulevards and direct roadways, created a larger sewer system, improved street lighting, and established city parks. Paris hosted its first Exposition Universelle in 1855, and then again in each decade until the century’s end (1867, 1878, 1889, and 1900), displaying the nation’s industrial and cultural products, and its colonial exploits from Indochina to Africa.

The Parisian music and theatre industry expanded. In addition to the city’s four opera houses (the Opéra, Opéra Comique, Théâtre Italien, and Théâtre Lyrique), there was spoken theatre at the Comédie Française and Odéon, and vaudeville, circus acts, and dance at the boulevard theatres. Hervé and Offenbach created their first operettas and opened new stages devoted to the tremendously popular genre, the Folies Nouvelles and the Bouffes Parisiens. In 1864 and 1867, Napoléon III revised the theatre legislation, greatly facilitating the opening of new theatres and giving them the freedom to explore different genres.

La ParisienneThe café-concert was the signature establishment of the period. Emerging out of the earlier café-chantants, goguettes, and working-class music bars and cafés, the café-concert became an important entertainment venue for both the working classes and bourgeoisie. Although admission was free, patrons were required to purchase drinks in order to sit and watch the performance. A typical evening began with spectacles de curiosités (acrobats, animal acts, dancing), followed by an instrumental interlude with excerpts from operas or operettas and fashionable dances (quadrilles, waltzes, polkas). The second part was devoted almost entirely to singers for the “tour de chant,” during which they would sing three to five songs. The evening ended with a short vaudeville or operetta; after 1867, café-concerts could even mount works with costumes and scenery. Many of the most popular and influential venues, Le Café des Ambassadeurs, l’Alcazar, l’Horloge, l’Eldorado, la Scala, l’Eden-Concert, and le Ba-Ta-Clan, were situated near the Champs-Elysées or on the grands boulevards on the Right Bank. By 1885, there were over two hundred café-concerts in Paris alone, directly and in-directly employing thousands of singers, actors, instrumentalists, costumers, composers, poets, and lithographers. The music publishing and printing industry supported the café-concert’s expansion and influence through the sale of sheet music, in-house journals, posters, illustrated programs, and songbooks.

La ParisienneThe café-concert was the signature establishment of the period. Emerging out of the earlier café-chantants, goguettes, and working-class music bars and cafés, the café-concert became an important entertainment venue for both the working classes and bourgeoisie. Although admission was free, patrons were required to purchase drinks in order to sit and watch the performance. A typical evening began with spectacles de curiosités (acrobats, animal acts, dancing), followed by an instrumental interlude with excerpts from operas or operettas and fashionable dances (quadrilles, waltzes, polkas). The second part was devoted almost entirely to singers for the “tour de chant,” during which they would sing three to five songs. The evening ended with a short vaudeville or operetta; after 1867, café-concerts could even mount works with costumes and scenery. Many of the most popular and influential venues, Le Café des Ambassadeurs, l’Alcazar, l’Horloge, l’Eldorado, la Scala, l’Eden-Concert, and le Ba-Ta-Clan, were situated near the Champs-Elysées or on the grands boulevards on the Right Bank. By 1885, there were over two hundred café-concerts in Paris alone, directly and in-directly employing thousands of singers, actors, instrumentalists, costumers, composers, poets, and lithographers. The music publishing and printing industry supported the café-concert’s expansion and influence through the sale of sheet music, in-house journals, posters, illustrated programs, and songbooks.

Women and the Spirit of France

Exoticism, Colonialism, and Paris

http://www.dutempsdescerisesauxfeuillesmortes.net

Angenot, Marc. Café-concert: Archéologie d’une industrie culturelle. Montréal: CIADEST, 1991.

Caradec, François, and Alain Weill. Le café-concert. 2nd edition. Paris: Fayard, 2007.

Chadourne, André. Les cafés-concerts. Paris: E. Dentu, 1889.

Condemi, Concetta. Les cafés-concerts. Histoire d’un divertissement. Paris: Quai Volaire Histoire, 1992.

Klein, Jean-Claude. La chanson à l’affiche. Histoire de la chanson française du café-concert à nos jours. Paris: Éditions Du May, 1991.

Leclercq, Pierre-Robert. Soixante-dix ans de café-concert, 1848–1918. Paris: Les belles lettres, 2014.