The Cheap Repository Tracts were a series of moral and religious tracts published between 1795 and 1798 by S. Hazard in Bath and J. Marshall in London. The series was conceived by evangelical writer Hannah More as an alternative to the vast amount of bawdy and irreverent chapbook and ballad literature that proliferated in the late eighteenth century. A strong proponent of literacy, More had personally helped to establish several Sunday schools. However, she was concerned that the newly literate lower classes were engaging in impertinent reading, and that such reading practices were responsible for sowing the seeds of political and social dissent. In the winter of 1794, she wrote to several community leaders and prominent evangelicals with copies of some moral tales she had penned along with plans for publication and distribution. These plans were met with enthusiastic approval and, in March of 1795, with £1000 in subscriptions, Henry Thornton acting as treasurer and Zachary Macaulay acting as agent, the Cheap Repository issued its first publications (Pedersen 84).

The Cheap Repository Tracts were a series of moral and religious tracts published between 1795 and 1798 by S. Hazard in Bath and J. Marshall in London. The series was conceived by evangelical writer Hannah More as an alternative to the vast amount of bawdy and irreverent chapbook and ballad literature that proliferated in the late eighteenth century. A strong proponent of literacy, More had personally helped to establish several Sunday schools. However, she was concerned that the newly literate lower classes were engaging in impertinent reading, and that such reading practices were responsible for sowing the seeds of political and social dissent. In the winter of 1794, she wrote to several community leaders and prominent evangelicals with copies of some moral tales she had penned along with plans for publication and distribution. These plans were met with enthusiastic approval and, in March of 1795, with £1000 in subscriptions, Henry Thornton acting as treasurer and Zachary Macaulay acting as agent, the Cheap Repository issued its first publications (Pedersen 84).

PN970 L86 W3 1814Unlike chapbooks, in which authorship is either obscured by multiple generations of unlicensed reprints or attributed to a collective folk tradition, it is relatively easy to recover authorship of Cheap Repository tracts. Of the one hundred and fourteen titles published by the Cheap Repository, Hannah More herself wrote approximately fifty; these are marked "Z". The rest were written by her sisters Sally (marked "S") and Patty More, or by fellow evangelicals Thornton, Macaulay, John Venn, John Newton, William Mason, Mrs. Chapone, and Selina Mills. Other titles were reprinted from "old favorites" (Pedersen 85) by Isaac Watts and Justice John Fielding, such as Divine songs: attempted in easy language for the use of children (1796). Structurally, Susan Pedersen asserts that the Cheap Repository tracts "follow a predictable formula. Most begin by describing a single central character, usually poor, who is put to some kind of trial. The character either responds well and is moderately rewarded or goes dramatically downhill and dies repenting" (Pedersen 88). When the Cheap Repository closed in 1798, John Marshall continued to publish tracts under its name, but these later tracts, possibly written by Marshall himself, were of an inferior moral character and "did not maintain the standard of piety set by More" (Pedersen 112).

The Cheap Repository is often discussed within the context of popular revolt that followed the French Revolution. More has been described as a political writer, and her earlier work, Village Politics (1792), which openly attacked Jacobinism and radical pamphleteers such as Thomas Paine, is often regarded as a precursor to the Cheap Repository. However, Pedersen has challenged this narrow political explanation, asserting that "the relatively few explicitly anti-Jacobin tracts in the Cheap Repository [are] virtually lost among the reams of Sunday readings, allegories, and little moral tales that attack vices ranging from drunkenness to superstition and that defy a simple political explanation" (Pedersen 86). She does not deny the political motivation for the Cheap Repository's inception—More had indeed been prompted to investigate the reading material of the lower classes by the flood of Painite literature—but asserts that it was the "vulgar and licentious" chapbook literature More encountered that convinced her to undertake the rather ambitious project of the Cheap Repository. In other words, More's tracts were "less an attack on Tom Paine than on Simple Simon" (Pedersen 87).

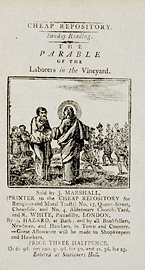

PN970 C52 no41aThe Cheap Repository tracts were intended to reach the rural poor through the normal channels of booksellers and hawkers, but they were also distributed by Sunday schools, charitable institutions, and, most importantly, by donation: More expected her fellow evangelicals to purchase the tracts in bulk and distribute them to the lower classes free of charge. In this last point she was not subtle—nearly every tract featured the following advertisement in one form or another: "Price One Penny, Or 4s. 6d. 100.-2s 6d. for 50.-1s. 6d. for 25". Clearly, these tracts were designed for wholesale, not retail. The price breaks were intended to encourage philanthropic individuals to make bulk purchases for donation and, in the early days of the Cheap Repository, such charitable endeavors were the only means of distribution. However, More was also eager to have the tracts sold through the normal range of booksellers and hawkers. In a circular announcing the plans for the Cheap Repository, she clearly outlined her intention of accessing the market in this way: "Let the experiment be fairly tried…Let the substantial dealer – let the retailer of papers and songs in the obscurer parts of a town – let those who occupy a stall at a fair for the sale of books and ballads – let the poor woman who travels with her matches and her cake – be all encouraged to try whether they cannot, at once, assist themselves and the cause of virtue" (More [qtd. in Neuburg {1977} 255-6]). More's prescription for potential distributors was twofold: they would benefit financially from selling Cheap Repository Tracts and, through their exposure to the social and religious message of these tracts, they would improve the overall moral welfare of themselves, their audience, and, by extension, society.

Despite encouraging charitable donations, More knew that wide-scale dissemination of the tracts depended on England's network of chapmen. In an effort to attract distributors, many tracts advertised that "Great Allowances will be made to Shopkeepers and Hawkers". Similar to the advertisements found in the back of chapbooks, the language is deliberately vague and leaves room for negotiation. The Cheap Repository was not profit oriented, but, even at wholesale prices, More was unable to undersell chapbooks to chapmen. In 1796, she wrote to Zachary Macaulay to inform him of her failure: "We were mistaken in believing them cheap enough for the hawkers. I find they have been used to getting three hundred percent on their old trash; of course they will not sell ours, but declare they have no objection to goodness, if it were but profitable" (More [qtd. in Pedersen 112]). It is difficult to calculate the profit margin of chapbooks because printers were deliberately vague about prices, but three hundred percent does not seem unreasonable. If More's tracts were considered too expensive at about a half penny each, which would have led to a mere one hundred percent return, it stands to reason that chapbooks were even cheaper. Many chapmen would indeed have carried Cheap Repository tracts from time to time, but this is a far cry from More's original intention of supplanting chapbooks as a staple of the chapman's pack.

Pedersen identifies four key characteristics of the Cheap Repository Tracts: First, "in style, language, and plot most were vivid and skilful propaganda" (Pedersen 97). Although the Cheap Repository was not the first "benevolent" scheme to attempt to reform the lower classes, it was the first to employ subterfuge as its primary tactic. Unlike The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, or the writings of evangelical moralists Sarah Trimmer, Maria Edgeworth, Dorothy Kilner, and Thomas Day, Hannah More's tracts were not overtly didactic. The format and titles were specifically designed to resemble chapbooks, but they carried a clear message of moral reform and social complacency. According to Pedersen, "[it] is the fact that the moral and social judgements are inextricable from the story that constitutes the tract's efficacy as propaganda" (Pedersen 89).

PN970 W38 W54 1795Second, in terms of content, the tracts condemned chapbooks and other forms of popular entertainment as "immoral pastimes" (Pedersen 97). Community life was generally seen as corrupt and, although the tracts idealized, and even praised, certain forms of local, organic community, they were suspicious of bad company and the dangers of the alehouse. For example, in The Wife Reformed, the immoral Mrs. Clacket, who represents bad company and idle diversions, is responsible for corrupting the titular wife and causing her to neglect her domestic duties. Similarly, in The History of Tom White the Postilion, the sober and industrious Tom goes from driving a wagon to the much more glamorous job of a postchaise driver and becomes utterly corrupted by the influence of gambling, drink, and loose company along the "Bath road".

PN970 S6 D6 1845Third, the tracts proposed an "alternative social structure" based on familial hierarchy and "vertical ties of moralization and dependence" (Pedersen 97). This is the most ambitious aspect of More's project of moral reform, and also the one for which she has received the most criticism. Her writing has been described as "the ideological justification for the economic exploitation and formal political exclusion of the poor" (Pedersen 85). The tracts encourage the belief that "the poor must passively await their salvation at the hands of the upper classes" (Stott 179). However, typically absent from the tracts is the real leader in rural societies, the squire. Instead, they frequently employ the arrival of some wise and benevolent clergyman as a means of resolving disputes and initiating moral reform. The "alternative social structure" proposed by such tracts established the framework for a "Christian commonwealth" (Pedersen 97). For instance, in the aforementioned The Wife Reformed, the corrupted wife is only able to see the error of her ways after being admonished by the good and pious Mr. Allen. In The History of Tom White, and its sequel The Way to Plenty, the townsfolk defer to the worthy vicar Dr. Shepherd as the arbiter of moral correctness.

PN970 C52 no47And finally, the Cheap Repository tracts subjected every aspect of public and private life to "moral surveillance" and subordinated earthly needs to the religious promise of "future glories" (Pedersen 97). The importance of moral surveillance is emphasized by tracts such as The History of Mary Wood, in which a young girl is plagued by many small, seemingly insignificant deceits that eventually lead to her ruin, and The Happy Waterman, in which the eponymous waterman refuses to keep a wallet he finds and is ultimately rewarded for his honesty. The promise of "future glories" is more pronounced in allegorical tales such as The Beggardly Boy and The Pilgrims, which maintain a strict hierarchy between "the things above" and "the things below".

Despite the Cheap Repository's relatively brief existence, the numbers were quite substantial. In the first two months they had printed and sold over 300,000 tracts, and, by the end of the first year, this number had increased to 2,000,000. However, because the tracts were purchased wholesale, it is difficult to determine how successful they were in reaching their target audience. The Cheap Repository was originally funded solely through subscriptions, but Hannah More had not anticipated the first year's success and the meager £1000 subscribed could no longer support such a high volume. In 1796, as part of a restructuring effort, More consolidated all printing operations under Marshall's firm in London. She raised additional capital by printing certain tracts in higher quality octavos and issuing bound volumes of the entire series for purchase by the middle and upper classes. Despite being subsidized for consumption by the lower classes, the Cheap Repository Tracts were most popular among the members of the gentry who were responsible for distributing them. According to Pedersen, it was within the sphere of wealthy elites that More's writing seems to have made the most difference: "The real success of More's tracts is to be found less in their conversion of the poor than in their effective recruitment of the upper class to the role of moral arbiters of popular culture" (Pedersen 109).

| < Prev | Next > |

![A new history of a true book : in verse. Cheap Repository ; [16c] PN970 C52 no 16c](images/sidebar_node011.jpg)