"The only figure who is more elusive in the whole trade than the chapman, is the man who bought from him" (Spufford 46).

Chapbook readership is difficult to determine because there is very little conclusive evidence. Until recently, a common approach was to assume—following Roger Davis and Victor Neuburg—that chapbooks were read exclusively by children and semi-literate adults. Richard Altick, for instance, asserts that the chief market for chapbooks was found among "apprentices, common labourers, peasants, [and] rivermen" (Altick 346). However, Matthew Grenby argues there is no way to "guarantee that the purchasers of chapbooks were from the lower classes" because, at the cost of a penny, chapbooks were "probably seen as a luxury...for [labourers] in Britain in the late eighteenth century" (Grenby 279). Unfortunately, due to a lack of first hand accounts, it is impossible to settle the matter decisively "by showing the humble reader actually in possession of ballads and chapbooks" (Spufford 45). There are, however, five streams of evidence that gesture—albeit indirectly—toward a large and socially diverse chapbook readership in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

PN970 K49 S4 1840Fictional accounts of readership and anecdotal evidence can often be misleading, but they help to establish what the contemporary assumptions about chapbook readership were. An often-cited example is Jerry Blackacre, the fictional lover of chapbooks from William Wycherley's The Plain Dealer (1677). Jerry longed to read such chapbooks as St. George for Chistendom and The Seven Champions of England, but his mother only permitted him practical guides and books of instruction for fear that chapbooks would have a negative influence on his moral development. Despite the mother's reluctance to indulge her son, this episode alludes to the popularity of chapbooks amongst children. Other fictionalized accounts of readership can sometimes be found in the woodcuts themselves. For instance, the frontispiece from one of Samuel Pepys's penny merriments depicts a "country yokel" purchasing a chapbook. However, despite the suggestive nature of this depiction, proof of readership is still "a very real problem" (Spufford 46).

PN970 D37 L5 1845

First hand accounts of readership tend to be more reliable, but they are notoriously rare. The act of reading leaves no trace and, unfortunately, chapbook readers were generally unwilling or unable to write about their experience: the former because they were "too well-educated to…record doing so," (Spufford 46) and the latter because they lacked the necessary writing skills. According to Jonathan Rose, the lack of first hand accounts has been the greatest obstacle for critics seeking to penetrate the mind of the humble reader. Although much scholarly work exists on the "experiences of professional intellectuals," (Rose 1) there is relatively little in the way of the British working classes. However, beginning in the 1980s, revised methodologies have allowed book historians to identify several sources of untapped evidence. Recent scholarly attention to cheap print has benefitted from evidence left in "memoirs and diaries, school records, social surveys…letters to newspaper editors (published or, more revealingly, unpublished), fan mail, and even in the proceedings of the inquisition" (Rose 1). These sources have been particularly helpful in uncovering evidence of chapbook readership amongst the lower classes.

Another promising approach is to check surviving records for evidence of chapbook circulation. Unfortunately, these records are often incomplete. Chapbooks were rarely preserved in collections and, although they once formed "the most considerable element in the printed popular literature of the eighteenth century," (Neuburg [1968] 3) the survival rate of chapbooks is incredibly low. A survey of 1500 probate inventories from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries revealed only five references to chapbooks. This does not mean that the two-penny chapbook did not exist, but, argues Spufford, that "they were not worth listing" (Spufford 48). Indeed, many chapbooks that sold for one or two pennies, which would certainly have been within the means of agricultural workers, were not recorded in inventories. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, Watt suggests that the increase in the number of sustainable publishers specializing in cheap print may itself "reflect an increase in awareness of lower social groups as a potentially lucrative market for print" (Watt 260).

A similar approach, employed by Jan Fergus, was to check the ledgers detailing book sales at Rugby School. She found that chapbooks formed twelve percent of total book sales between 1744 and 1784. However, in addition to being limited by social class, this approach only takes one aspect of the market into account—it assumes readership based solely on book sales. Practices of sharing make it difficult to determine readership in this way because there is no record of how many people read any given book once it has been purchased. Furthermore, because the records only list books that were bought on credit (not purchased with cash or from outside sources), it is likely that Rugby’s chapbook readership was much higher than the numbers indicate.

PN970 K4 S45 1800zOne of the greatest factors affecting chapbook readership was literacy. David Cressy's literacy statistics, which indicate a male literacy rate of at least 30 percent in 1642, and 60 percent by the mid eighteenth century, have often been cited as evidence of a "market for cheap print" (Spufford 45). Landowners and the lesser gentry were already 65 percent literate by 1642, which means that this increase in literacy was most acute in the lowest sections of society. Susan Pedersen concludes that, because this new class of readers was composed greatly of "labourers and servants," chapbooks were the "only publications within the means of this literate populace" (Pedersen 99). This period also witnessed a rise in specialized printing houses, which suggests that writers and publishers of the 1630s "were increasingly aware of these new readers as literacy progressed" (Watt 294).

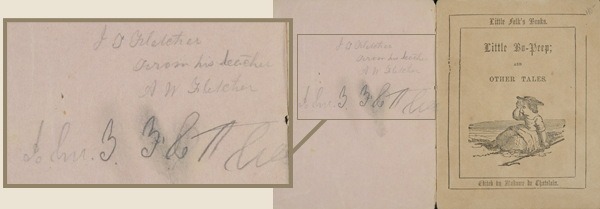

PN970 R4 S55 1822In the absence of direct evidence, many critics have attempted to deduce chapbook readership by analysing the content. Spufford asserts that, although chapbooks were typically intended for a very broad audience, some were aimed at specific groups within the community. Chapbooks that ridicule the "clodhopping countryman" (Spufford 51) would most likely have been aimed at an urban readership, while chapbooks such as The Country Mouse and the City Mouse, and Cawwood the Rook—which both carry the moral that "it is best to be poor, but contented" (Spufford 57)—would clearly have been composed "with the country reader in mind" (Spufford 56). In terms of age and gender, she assumes an intended readership of young males for stories of apprentices, such as Aurelius, the Valiant London Prentice, and John and His Mistress, and adolescent girls for a sentimental chapbook like Country Garlands. However, this method is ultimately flawed because, despite the best efforts of publishers to appeal to specific groups, there is no way to confirm whether the intended readership correlated with actual readership; as Grenby points out, "old men might have happily read of young girls" (Grenby 282).

PN970 S6 D6 1845 Although none of these sources provide conclusive evidence of readership, they are consistent with Neuburg's assertion that chapbooks constituted the most significant aspect of "printed popular literature" in the eighteenth century. However, warns Tessa Watt, the term 'popular literature' is misleading if it is meant to imply that chapbooks were "exclusive to a specific social group" (Watt 1). This rather important caveat is central to a broader understanding of the social and literary impact of chapbooks because, while it is true that chapbooks constituted "almost the entire reading matter of the poorer classes in eighteenth-century England," (Neuburg [1968] 2) it does not necessarily follow that chapbook readership was restricted to the poorer classes. The division of society into mutually exclusive 'elite' and 'plebeian' subcultures fails to account for the elite's "frequent participation in…the 'little tradition'" (Grenby 279). The 'great' tradition was "the closed culture of the educated elites," (Watt 2) but the 'little' tradition—"popular festivities, popular rituals, and popular literature" (Grenby 279)—was "open to everyone, including those elites" (Watt 2). In other words, says Grenby, "aristocrats read chapbooks...even if the lower classes could not 'reciprocate' by reading those texts that required a formal education" (Grenby 279). As cultural artefacts that were read and enjoyed at all social levels and in all classes, chapbooks exemplify what Martin Ingram has described as an area of "cultural consensus" (Watt 2). Unlike "vertical antagonisms," such as religion, which divide society at all levels, areas of cultural consensus constitute a uniformity of values or beliefs across the entirety of the social strata. This is rather remarkable because, unlike the traditional cultural dynamic in which elite and plebeian cultures were thought to practice mutual exclusion, chapbooks promote a form of cultural sharing—albeit unreciprocated—in which the aristocracy engage with literature that is inculcated with a "plebeian moral economy" (O'Malley 20).

| < Prev | Next > |