PN970 T44 C87 1799

The most remarkable aspect of the chapbook, and one by which it has often been defined, is the method of distribution. Chapbooks were carried and sold by itinerant pedlars known as chapmen who "travelled the length and breadth of England" selling their wares (Neuburg [1968] 30). The typical chapman had "a long pack, partly open, suspended from his neck," (Weiss 1) in which he carried a wide range of goods. Also known as "hawkers," "pedlars," or "flying-stationers," chapmen were the "only merchants in rural districts in early times" (Weiss 1). They purchased their wares from large wholesalers—or direct from publishers—in London and travelled along familiar routes, often passing through remote areas that had restricted access to markets. A vital link between town and country, chapmen were responsible for bringing chapbooks and other forms of cheap print to "the farming communities, the shepherds, the labourers in remote parts of the country where there were no bookshops" (Roscoe 97). Readers in villages and market towns in East Anglia in the late seventeenth century would have been greatly dependent on itinerant pedlars because there were no bookshops outside the "six largest towns in the region at this time" (Stoker 114).

http://www.otago.ac.nz

Many London chapbook publishers were also booksellers, but their advertising was aimed almost exclusively at their distributors, the country chapmen. They established their shops in two main concentrations—the West Smithfield Market and London Bridge—which was where chapmen congregated. Deacon, for instance, was quite unambiguously addressing potential distributors when he ended a 1686 quarto, "Courteous Reader, these Books are Printed for, and sold by, J. Deacon, at the sign of the Angel in Guiltspur Street; where any Chapman may be Furnished with all sorts of small Books and Ballads" (Spufford 111). A similar advertisement from John Back included a list of available titles which, he announced, were all "Books printed for and sold by J. Back at the Black Boy on London Bridge, who Furnisheth any Countrey-Chapman, with all sorts of Books, Ballads, and all other Stationery-Wares at reasonable Rates" (Spufford 111). The promise of "reasonable rates" was deliberately vague because the price often depended on the quantity purchased. Neuburg recounts how Sir Joseph Banks's sister, "herself a collector of chapbooks," attempted to pay a shilling for a dozen penny books and "was given threepence change and told to take two more." The vendor had mistaken her for a trade customer and was offering her the standard rate of "thirteen or fourteen to the dozen for ninepence" (Neuburg [1968] 30-31). Anecdotal evidence such as this can provide some context, but a more comprehensive guide to wholesale chapbook prices can be found in the catalogue issued by Dicey and Marshall in 1764. In this catalogue, 'Penny History Books' are priced at "One hundred and four for two shillings and sixpence," while 'Small Histories,' or 'Books of Amusement for Children,' are a bit more expensive at 100 for six shillings (Neuburg [1968] 31).

http://www.otago.ac.nz

Many London chapbook publishers were also booksellers, but their advertising was aimed almost exclusively at their distributors, the country chapmen. They established their shops in two main concentrations—the West Smithfield Market and London Bridge—which was where chapmen congregated. Deacon, for instance, was quite unambiguously addressing potential distributors when he ended a 1686 quarto, "Courteous Reader, these Books are Printed for, and sold by, J. Deacon, at the sign of the Angel in Guiltspur Street; where any Chapman may be Furnished with all sorts of small Books and Ballads" (Spufford 111). A similar advertisement from John Back included a list of available titles which, he announced, were all "Books printed for and sold by J. Back at the Black Boy on London Bridge, who Furnisheth any Countrey-Chapman, with all sorts of Books, Ballads, and all other Stationery-Wares at reasonable Rates" (Spufford 111). The promise of "reasonable rates" was deliberately vague because the price often depended on the quantity purchased. Neuburg recounts how Sir Joseph Banks's sister, "herself a collector of chapbooks," attempted to pay a shilling for a dozen penny books and "was given threepence change and told to take two more." The vendor had mistaken her for a trade customer and was offering her the standard rate of "thirteen or fourteen to the dozen for ninepence" (Neuburg [1968] 30-31). Anecdotal evidence such as this can provide some context, but a more comprehensive guide to wholesale chapbook prices can be found in the catalogue issued by Dicey and Marshall in 1764. In this catalogue, 'Penny History Books' are priced at "One hundred and four for two shillings and sixpence," while 'Small Histories,' or 'Books of Amusement for Children,' are a bit more expensive at 100 for six shillings (Neuburg [1968] 31).

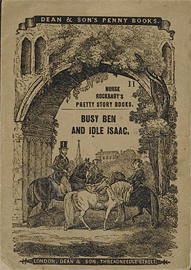

PN970 B66 N87 1780

PN970 L86 L6 1814

The early book trade had been centered almost entirely in London, and the chapman was often the only discernible link between chapbook printers and their "widely scattered public" (Neuburg [1964] 3). The scarcity of rural printing houses meant that chapmen had to travel great distances in order to reach rural audiences. Indeed, the chapman's very livelihood often depended on his ability to effectively navigate the fairs and markets of provincial trade routes, which gave rise to a number of publications intended to aid him. The first was The City and Country Chapman's Almanack, published in 1687. Although there had been similar books designed for travelers, this was the first one that was directed specifically at chapmen, and included "distances between towns and villages," as well as "details of fairs and markets held throughout the country" (Neuburg [1968] 33). Later guidebooks include The Chapman's and Traveller's Almanack (1693), which was reprinted in 1694 and 1695, and The English Chapman's and Traveller's Almanack (1696), "which was reprinted up to 1712" (Neuburg [1968] 32). These guides were particularly important in the early years of the book trade, but by the early eighteenth century, rural publishing houses had become much more numerous. This allowed chapmen to travel greater distances and reach wider audiences because they could replenish their stock from a local printer without making the long journey back to London. One of the greatest problems that early chapmen faced was, ironically, having too much money. When a chapman set out with a pack of goods, he often traveled a familiar circuit that could take any number of days or weeks to complete. If he sold his stock too quickly he was no longer carrying goods, but money, which was "unprofitable as well as dangerous, as the money was standing idle" (Morris 172). It was therefore common for chapmen to buy new commodities along their trade routes, and this was greatly facilitated by the spread of rural printing houses.

PN970 B66 C46 1780The chapman was an important figure in rural communities because, in addition to carrying chapbooks and broadside ballads, they also carried important household items such as ribbons, needles, thread, fabric and spices. The chapman was often the only source for such items in isolated communities. Furthermore, the chapman functioned as an important social link, carrying news and gossip between isolated farm communities and the outside world (Neuburg [1964] 1). However, despite all of these benefits, the country chapman was often regarded with suspicion and distrust. Referred to as "unruly" in old laws, chapmen were frequently "chased by dogs and slept with the pigs or in the barn" (Weiss 1). Because they traveled through areas where there "were no regular inns or lodging houses," (Morris 169) chapmen often depended on the kindness of their customers for board and lodging. The most they could hope for was usually a lick of the porridge ladle and a straw bed in exchange for a few trinkets or perhaps a song. It was often the case, however, that chapmen would be "turned out to find [themselves] a ditch" (Morris 170).

PN970 R87 L54 1840In 1696-97, an Act requiring the mandatory licencing of pedlars, hawkers, and chapmen was passed. Technically, a pedlar travelled on foot, whereas a hawker sold his goods "from horseback or from a horse and cart" (Stoker 115). Although these terms are often used interchangeably to refer to chapmen, the licence cost £4 a head "for both man and beast," (Spufford 116) which meant that hawkers were actually charged more. According to Spufford, any pedlar, hawker, or chapman caught operating outside a market or fair without a licence could be fined £12. In the first year alone, over 2550 chapmen were licenced, however, the number of those who evaded the tax was likely much higher. Susan Pedersen estimates that, by 1700, "there were about 10,000 such pedlars throughout England" (Pedersen 98). Although chapbooks certainly "enjoyed a very wide circulation," (Neuburg [1968] 30), these figures can easily mislead because not all chapmen carried cheap print and, amongst those who did, there were varying degrees of specialization. The British Book Trade Index indicates an incredibly high prevalence of chapmen in the seventeenth century, but the records do not specify whether they were "associated with the sale of reading matter" (Stoker 116). Watt asserts that, in the sixteenth century, chapmen specializing in cheap print "were probably much less common…than those carrying [cheap print] as a sideline with other wares" (Watt 27).

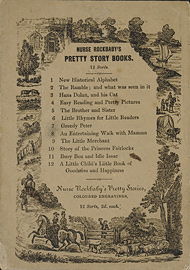

PN970 D4 B8 1847

PN970 D4 B8 1847

| < Prev | Next > |