PN970 P37 P38 1836

PN970 O7 C4 1853

PN970 B56 P5 1827

PN970 P37 P37 1836

PN970 D63 C63 1829

PN970 D4 C3 1857

PN970 D63 C63 1829The manufacturing center of the English book trade has always been London and, in this regard, chapbooks were no exception. During the seventeenth century, England's book trade was controlled by a handful of powerful London firms belonging to the Company of Stationers, with very few provincial printers or publishers. However, when the 1662 act limiting the number of Master Printers expired in 1695, the number of printing houses dramatically increased. According to William St Clair, "the number of active presses rose by at least 400 per cent" in London during the eighteenth century (St Clair 87). Expediency was the guiding principle of chapbook production, and printers did not hesitate to steal the work of rival presses (Weiss 1). Amongst the earliest chapbook printers were John Wright, John Clarke, Thomas Passinger, and William Thackeray, with a second group, "frequently ex-apprentices of the first," consisting of Philip Brooksby, Jonah Deacon, Josiah Blare, and John Back (Spufford 83-4). There was also a significant increase in the number of provincial printing houses, but cutthroat publishing tactics combined with the virtual non-existence of copyright laws meant that provincial chapbooks were virtually identical to those printed in London. It was not until the 1710 copyright act (Statute of Anne), which granted a fourteen-year copyright to the author of a work, that authorial right was "made explicit in the statute law of Great Britain" (St Clair 91). However, as was often the case, the new copyright laws were to the benefit of the publisher, not the author, who would usually sell the rights to their work for a nominal stipend.

Despite the incredibly high number of urban and rural printing houses, the Dicey press at Aldermary Churchyard remained the center of chapbook manufacturing for much of the eighteenth century (St Clair 340). In 1720, William Dicey and Robert Raikes established The Northampton Mercury and started printing chapbooks. In 1725 Dicey became sole owner; in 1732 he took his eldest son Cluer as a partner and "for more than half a century the Dicey family were the largest producers of chapbooks" (Neuburg [1968] 27). During this period, the Diceys were responsible for "a variety of imprints, including over 150 chapbook titles"(Pedersen 98). William Dicey began printing ballads and chapbooks with an "obvious indebtedness" to James Roberts' A Collection of Old Ballads (1723), from which he derived "a good part of his ballad stock" (Dugaw 75). During the high monopoly period (1710-1774), the Diceys "held the intellectual properties, the unsold stocks, and the manufacturing plant, in all the favourite titles" (St Clair 341). Although the Statute of Anne only granted a fourteen-year window of copyright protection, many publishers operated as though they owned the rights to their catalogue in perpetuity. Cluer became the sole owner upon his father's death in 1756 and, although it is unlikely that he was still printing chapbooks, Thomas Dicey, inherited the business when Cluer died in 1775 (Neuburg [1977] 109-10).

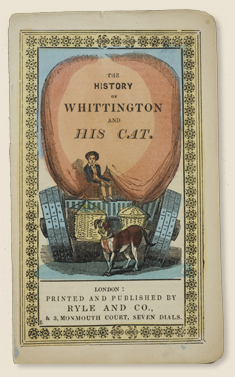

PN970 R95 L5 1821By the end of the eighteenth century, sales dwindled as chapbooks had "begun to go out of fashion amongst adult readers" Neuburg [1968] 59). Many provincial publishing houses continued to print children's chapbooks in the first decades of the nineteenth century, but, by this time, the chapbook was "no longer the most important element in popular culture; it was now entirely intended for child readers" (Neuburg [1968] 65). However, chapbooks experienced a considerable revival in the early nineteenth century, when "James Catnach replaced the Diceys as the king of the chapbook printers" (Pedersen 98). What the Diceys were to eighteenth century chapbooks, Catnach was to nineteenth century street ballads and, although none of his publications were original (Neuburg [1968] 71), the output of his presses was considerable (Neuburg [1968] 68). Catnach was born at Alnwick in 1792. In 1813, he set up as a jobbing printer at No. 2 Monmouth Court, Seven Dials and, although Catnach himself died in 1841, his business "[flourished] in the hands of his successors for well over fifty years" (Neuburg [1977] 140).

PN970 M37 H57 1835

PN970 D37 L5 1845

PN970 D4 D4 1857 no 15

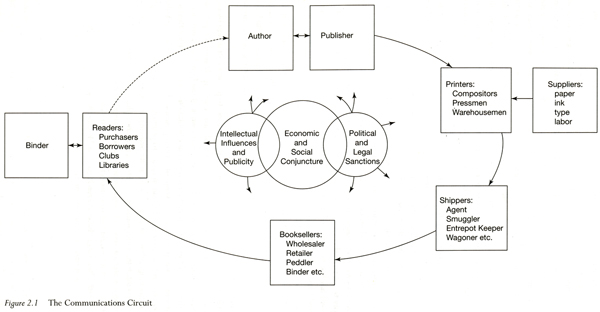

By the nineteenth century the publishing industry had become highly specialized and, as a result, highly compartmentalized. In order to illustrate the typical conditions under which books were produced it is worth turning to Robert Darnton's "communications circuit" (Darnton 12), which describes the interactivity between the six phases of a typical book's life cycle: from authorship to publication to printing to shipping to the booksellers and, finally, the readers. However, there are cases in which considerable overlap between these phases can obscure the details of a book's publication. For example, Darnton suggests that, "the evolution of the publisher as a distinct figure in contrast to master bookseller and the printer still needs systematic study" (Darnton 18). This is particularly true of chapbooks, in which "the distinction between printer, publisher and bookseller is often so blurred as to be virtually non-existent" (Neuburg [1968] 21). Without the need for expensive bindings, detailed engravings, or even covers, chapbooks could be printed, assembled, and sold by the same individual. In this regard, many chapbook printers were also the publishers, wholesalers, and retailers and they sold their wares "retail to individuals and wholesale to chapmen" (St Clair 340), without the need for costly intermediaries. In rare cases, the printer was also the author, which condenses the entire communications circuit into one individual, save the reader—although authors are also always readers.

"What is the History of Books?" The Book History Reader.

| < Prev | Next > |