Although critics disagree about the exact role that chapbooks played in promoting literacy, most are willing to concede that there is a positive correlation between the proliferation of cheap print and periods of increased literacy. For example, Victor Neuburg has suggested that the chapbook is itself a "manifestation of the growing interest in books" (Neuburg [1968] 5). Similarly, Tessa Watt argues that, because chapbooks were not "as adaptable to oral and visual uses as the broadsides," they reflect a trend in authorship towards a "wholly literate form" (Watt 320).

The closest approximation of actual literacy rates in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries comes from David Cressy's survey of political and religious registries. Cressy's literacy statistics are based on the percentage of those who signed their name, rather than simply indicating assent by leaving a mark. According to the number of signatures recorded by the Protestation Oath of 1641, the Vow and Covenant of 1643, and the Solemn League and Covenant of 1644, Cressy estimates a male literacy rate of at least 30 percent. After 1754, the marriage registers of the Church of England, which required the signatures of both bride and groom, indicate a male literacy rate of at least 60 percent (Chartier 119).

PN970 K4 L68 1820However, because the small number of children who attended school "learned first to read and then to write," (Chartier 118) it is likely that Cressy's statistics grossly underestimate the number of those who could actually read. Very few children stayed in school until age eight or nine when writing was taught because that was also the age at which paid labour commenced. Margaret Spufford has argued that the ability to sign one's name can therefore be tied conclusively to social status because a certain amount of prosperity was necessary to spare a child from the labour force long enough for he or she to learn to write. In other words, although everyone who could sign could most likely read, "not everyone who knew how to read could sign his name" (Chartier 118). With these drawbacks in mind, many critics are still willing to accept Cressy's figures as a "rough, composite index" (Chartier 119). Watt argues that Cressy's literacy statistics "should be taken as minimum figures, not as certainties," and that, because reading was taught before writing, "it is likely that many more rural people could get through the text of a broadside ballad than could sign their names to a Protestation Oath" (Watt 7). Despite Cressy's inability to provide accurate literacy rates, most critics agree that, by the closing years of the eighteenth century, "a large reading public had become a reality" (Neuburg [1964] 3).

PN970 E55 F57 1830The end of the eighteenth century, which witnessed the peak of chapbook publications in England, also saw "male literacy rates [rise] 30 percent higher" (Chartier 119) than they had been a century and a half earlier. The exact nature of this relationship has been interpreted in three ways. A common hypothesis has been that publishers were merely responding to market conditions that they had no hand in creating; increases in literacy caused an increase in the demand for cheap print, and publishers met this demand "by printing broadsides, ballads and chapbooks." (Weiss 2) Tessa Watt uses a similar logic when she cites the popularity of chapbooks in rural areas as evidence of how "literacy in the countryside was progressing" (Watt 320). However, as attractive as it seems, this approach fails to account for the role that chapbooks actually played in promoting literacy.

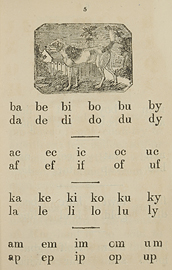

An alternative approach, and one which has gained popularity in recent years, is to invert the relationship between chapbooks and literacy; that is, to view the wide-scale dissemination of cheap print as generating its own reading base. Access to reading material played a critical role in the spread of literacy and, since it is generally assumed that chapbooks were also used to teach children to read (Grenby 283), it logically follows that an increase in the availability of cheap print would help promote literacy.

PN970 R87 H57 1820

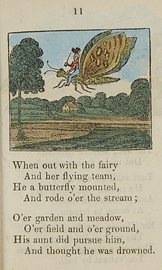

A third, and perhaps more promising approach is to acknowledge the reciprocal nature of the relationship between cheap print and literacy. Such popular chapbook titles as "Guy, Earl of Warwick," and "King Arthur" can be traced back to the Middle Ages where they appeared in manuscript form as late as 1400. These texts were first printed as books in the early sixteenth century and, originally intended for a gentry audience, they were later abridged into "cheap and affordable" broadside ballads (Watt 257). By the early eighteenth century, however, these same stories were being adapted back into book form "for country buyers" (Watt 257) by such prominent chapbook publishers as John Pitts (1765-1844) of Seven Dials and Cluer Dicey (1715-1775) of Aldermary Churchyard. Tessa Watt argues that the "dialectic between song and book versions reflected changes of audience and growing literacy within each social group" (Watt 257). In other words, as stories fluctuated back and forth between song and book, they embodied whatever form of popular culture was in vogue at the time. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries this was the ballad, which appealed to semi-literate adults because it could be sung or heard sung. By the eighteenth century, however, this was more frequently the chapbook, a form which lent itself to reading, and which could also be read aloud for the benefit of those who could not read for themselves.

| < Prev | Next > |