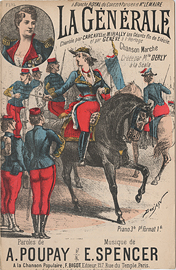

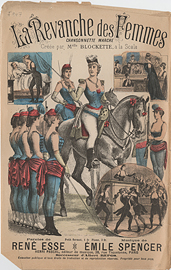

You might call her a priestess ordained, and bringing up human sacrifices to lay on the altar of glory; or again might see in her form a conventional image of France nobly leading her sons into action, and commanding them, if need be, to die. Each actress had her own “reading” of the part that she played.

– Cardoza, Intrepid Women (2010, 153).

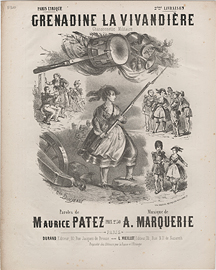

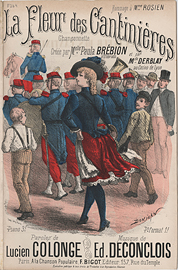

Throughout the nineteenth century, women participated in the French army as vivandières (at times called cantinières, or sutlers in English). In addition to serving food and drink to the soldiers, they frequently assumed the role of nurse and even engaged in military action, challenging contemporary understandings about femininity. Appearing in numerous popular images as well as in various instantiations on stage (from operas, such as Donizetti’s La fille du regiment, to theater and ballet), vivandières were part of the iconography of military life. As Lynn writes, “pretty images became something of a fixture in artists’ renditions of camp life” (2012, 117).

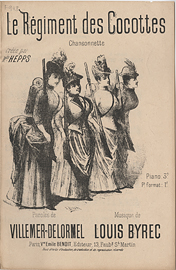

Vivandières would accompany a regiment and they were often married to one of the soldiers. Although at times associated with prostitution, Cardoza (2010) argues there is little evidence to substantiate vivandières working as prostitutes within the army. Nevertheless, with the tight-fitting military clothing that emphasized their busts and legs, inviting the male gaze, the viviandière was often a sexualized figure. This was particularly the case with staged performances, but also true of the images of vivandières depicted on sheet-music covers. The cross-dressed woman disguised as a male soldier was another popular subject. She was sexually titillating, yet by exhibiting what theorist J. Halberstam calls “female masculinity” (1998) she was also a threatening figure within the context of changing gender roles. Toward the end of the century, vivandières gradually disappeared from the military, and by 1906 the profession ceased to exist. Nevertheless, the image of the woman in uniform endured in the public imagination.

Café-concert and salon repertoire celebrated the vivandières, while simultaneously fostering nationalistic pride. In his work on musical semiotics, Raymond Monelle (2006) identifies the march and the trumpet call as the two primary signifiers of the military. Most songs featuring vivandières are upbeat marches and include musical motifs evocative of the military: fanfares, dotted eighth-note rhythms, and triadic leaps that imitate trumpet calls in either the vocal line or the accompaniment.