About The Canadian War Posters Collection

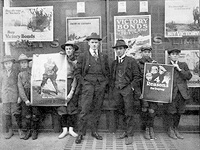

The modern, mass-produced poster was made possible by the invention of the lithographic process in 1798. These large, boldly lettered, and eventually colourful, advertisements and announcements, presented to the viewer on vertical surfaces and at eye-level, would have a far more immediate and powerful effect on a public accustomed to handbills and advertisements in newspapers and magazines. By 1890, in Canada, broadside posters were widely circulated and used for a variety of purposes, including government announcements. The recruiting and financing needs of the First World War demanded that governments produce more posters than ever before. Canadian posters for the First World War (as well as for the Second World War) were printed in the major printing centres of Hamilton, Montreal, and Toronto. According to Marc Choko's authoritative book, Canadian War Posters (Meridien 1994), print runs of Canadian war posters ranged anywhere from a few hundred to 50,000 copies. These images created a powerful impact in a variety of public places, from store windows and billboards to the interiors of ferries and factories.

During the First World War, the imagery of Canada's posters was, both thematically and graphically, similar to that of British war posters.This visual affinity was partly due to the imperial and constitutional ties between Canada and Britain.In addition, Canada targeted posters at specific ethnic groups. There were specially designed posters for French Canadians, Irish-Canadians and Canadians of Scottish descent. The bulk of the posters encouraged men to enlist and the public to buy Victory Bonds.

In the Second World War, Canadian posters reflected the fact that Canada was not under attack by an aggressor on its own turf. Whereas some countries' war posters portrayed violence in graphic detail, Canada's posters generally avoided such direct images. While war posters again encouraged enlistment and financial support of the war effort, advancements in communication made appeals for discretion and secrecy staple messages of many Second World War posters. Another frequent theme was the encouragement of workers to increase productivity.

There was no central government agency in charge of all war poster production during the First World War. In 1916, the federal government did establish the War Poster Service which produced some posters in both English and French. The French posters were often translated versions of the English original designs. Some well-to-do civilians and private companies produced their own posters in aid of the war effort and individual regiments often issued their own recruiting posters. The Canada Food Board published posters toward the end of the war urging citizens to produced and conserve food. Second World War poster production was centralized under the Bureau of Public Information, which was subsumed by the Wartime Information Board in 1942. As was the case earlier, some private companies, the House of Seagram for example, and individual citizens continued to publish posters in the interest of the Second World War effort.

War posters aimed to impart a clear message to the viewer. Whether a poster encouraged the purchase of Victory Bonds or discouraged talk of Allied troop movements, its mission was to convey a specific message that could be interpreted only one way. The methods by which posters imparted their messages were different in each of the World Wars. In the First World War, posters were beset with text, while Second World War posters more effectively used emphatic slogans and intense graphics. Overseas Battalion 148 Now Recruiting, a First World War poster designed by the architect and artist, Percy Erskine Nobbs (1875-1964), offers an image of an officer slaying a German eagle. Compared to Allons-y Canadiens, a Second World War recruiting poster by Henri Eveleigh (1909-present), the Nobbs poster has less colour, more text, and less emotional impact. The officer is without expression as he slays the symbolic eagle. In contrast, the soldier in the Eveleigh poster charges toward the viewer, brandishing his weapon, an expression of intense emotion on his face. The simple text, Allons-y Canadiens, is splashed in bold letters across the lower quarter of the poster. This is not merely an invitation to join the army, as was the case with many First World War posters, but a passionate command. During the Second World War, more effective appeals were made through posters, partly because the world had already experienced the horrors of one world war, and also because advertising experience and contemporary studies had shown that dramatic and emotional appeals were more effective methods of reaching the Canadian public. A study by the Young and Rubicam agency of Toronto in 1942 found that the most effective posters were purely emotional, "appealing to sentiment through realistic images with photographic details, accessible to millions of middle-class citizens" (Choko 1994). The study found that symbolism and humour were considered ineffective by the public. The artists who designed war posters ranged from anonymous graphic artists to well-known Canadian painters and for this reason Canadian war posters present a wide variety of styles. Sometimes the artists were winners of war poster design competitions which were held during both wars. The need to find effective imagery for posters gave many artists and graphic designers a new opportunity to hone and expose their talents. Montreal-born and -trained architect and painter, Harry Mayerovitch, was one such poster designer. He worked in Ottawa from 1942 to 1944 and created a number of posters for various war- time campaigns under the pseudonym "Mayo". He won the first and third prizes for Canadian war posters in 1944.

Canadian war posters were produced for a specific audience and for specific purposes. They were not meant to be archival or historical documents, but because of their time and place specificity they have become an important resource through which today's researchers and interested public can explore aspects of wartime life. Canadian war posters present the modern viewer with seemingly dated and distant images, yet they convey both the intensity and the immediacy of a by-gone era.