Both men and women read the Books of Hours, although there are some who still insist that they were primarily the favourite devotional reading for women in their homes. However, this assumption requires some clarification: in Lacité des dames, written at the very beginning of the 15th century, Christine de Pisan painted a picture of the sincere piety of women and noted that they read Books of Hours not only in their homes but also took them to church rather than a missal.

Furthermore, as the pieces in this exhibition show, women were involved to a greater or lesser extent in the production of these books.

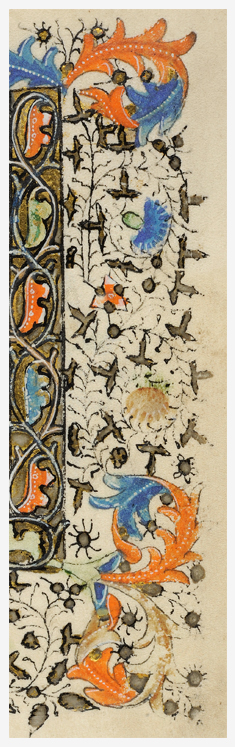

- Officium beate Marie secundum usum Romanum, a manuscript Book of Hours with trompe-l’oeil borders in the style of Ghent and Bruges, was illuminated in about 1500-1510 by Cornelia van Wulfscherchke, a Carmelite nun in Bruges. McGill MS109.

- In the Rhodes Hours, the patron is painted kneeling right in the middle of the illumination of the Annunciation in a scene that combines the sacred and the profane, while the Marian prayer Obsecro teis couched in the feminine voice (famula tua). McGill MS155.

- Renée de Bourbon, Duchesse de Lorraine, commis-sioned Pierre Gringore to translate into French the Heures de Nostre Dame, published in 1525. McGill European Prints 8vo 309.

- Some leaves of the psalter-breviary for the use of the Brigittines of the Mariënwater abbey in Brabant may well have been painted by the nuns, since their scriptorium of illuminators and copyists included both men and women. McGill MS151.

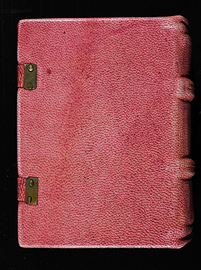

MS 109. Book of Hours for the use of Rome. Flemish, c. 1500-1510

MS 109. Book of Hours for the use of Rome. Flemish, c. 1500-1510Credits: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts / Musée de beaux-arts de Montréal for permissions to use texts prepared by Brenda Dunn-Lardeau et Richard Virr for the 2018 exhibition: Resplendent Illuminations: Books of Hours from the 13th to the 16th Century in Quebec Collections / Resplendissantes enluminures : Livres d’Heures du XIIIe au XVIe siècle dans les collections du Québec.