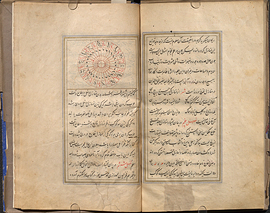

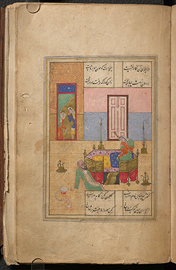

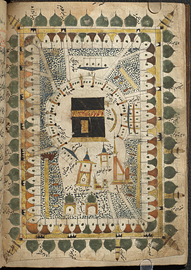

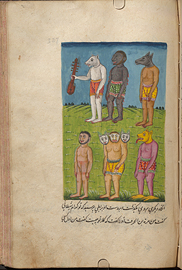

Persian painting and the arts of the book continued to evolve throughout the Safavid Period. The 17th century CE saw a growth in popularity of single paintings commissioned by individual wealthy patrons, which could be later collected into albums. Although he worked as a miniaturist for the Safavid court in Isfahan, Rizā-i ‘Abbāsī also became the most famous painter of single portraits—particularly those of stylish youths—a style continued by his pupils and many imitators. The Persianate arts of the book were not limited only to the spheres of poetry, belles-lettres and portrait painting, however. Rather, in the Safavid Empire and beyond, native speakers of Persian as well as those who had adopted the language used it as a vehicle for works of philosophy, theology and the natural and hard sciences. While many volumes were of course translated from Arabic, the traditional language of Islamicate civilization, original Persian works on astronomy, astrology, biology, history, law and medicine, as well as the ‘ajā’ib genre on strange and marvelous things were composed as well. Interest in travel narratives, such as Muḥyī al-Dīn Lārī’s guide to the rituals of the annual Ḥajj pilgrimage and to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, Futūḥ al-Ḥaramayn, transcended ethnic and linguistic boundaries and was copied and circulated across the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia.