The term "lithography" comes from two ancient Greek words: "lithos" (λιθος) meaning "stone" and "graph" (γράψ) meaning "write". Printing by lithography was invented in 1796, in Germany, by Aloys Senefelder (1771-1834), an actor and playwright who wanted to be able to print his own plays. The technique consists of applying, often by hand, an oil-based text or image on the surface of a smooth piece of limestone1. Then a solution of Arabic gum2 in water was applied to the non-oily surface, and finally, during printing, the water-based ink adhered to the Arabic gum surfaces avoiding the oily parts.

At the end of the eighteenth century, lithography was brought to France and England, where it always remained a subsidiary method for book printing. In contrast, printing by lithography quickly spread to the Islamic World where it was received with enthusiasm. Although scholars are not always in agreement when it comes to explaining Muslims' preference for lithography over other printing techniques, three main reasons3 are often invoked:

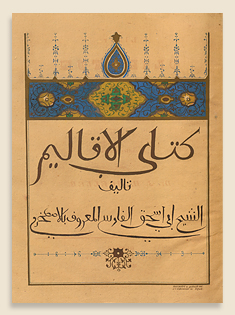

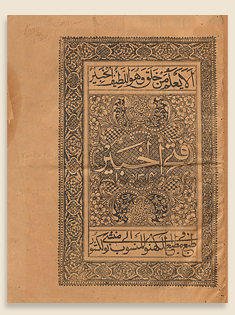

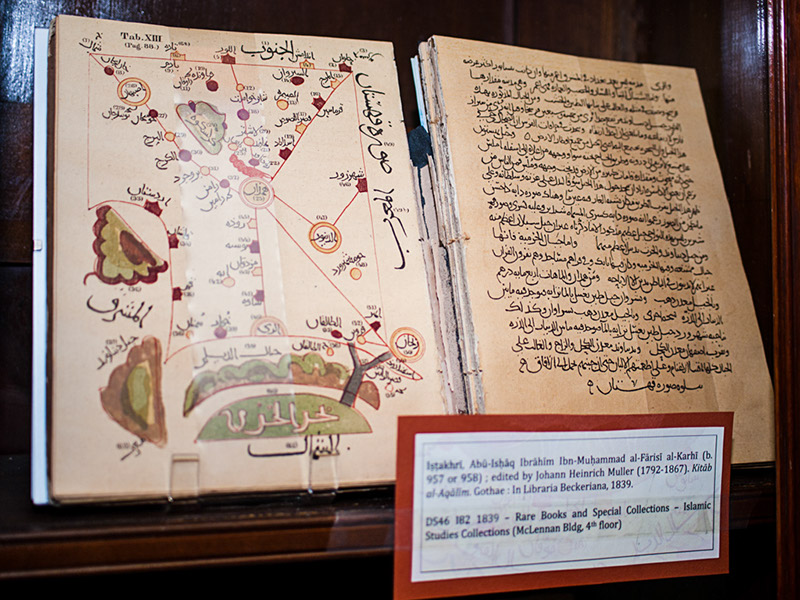

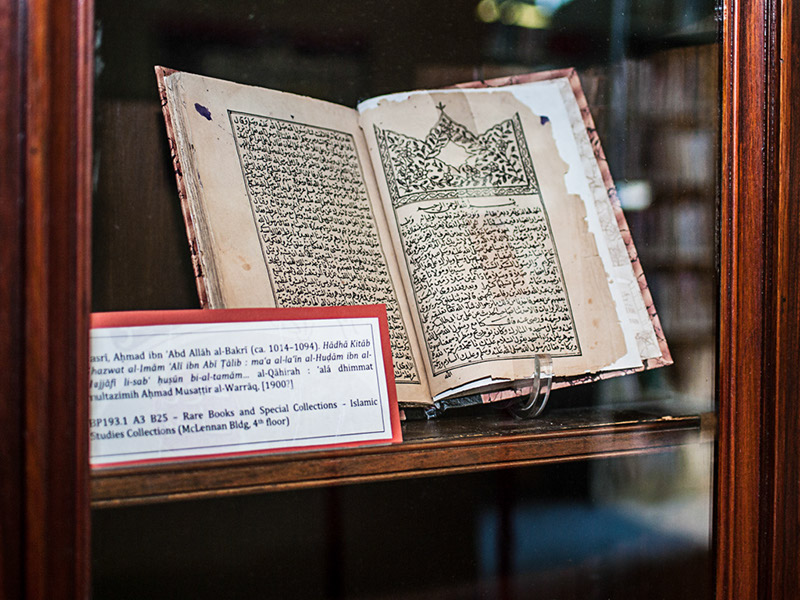

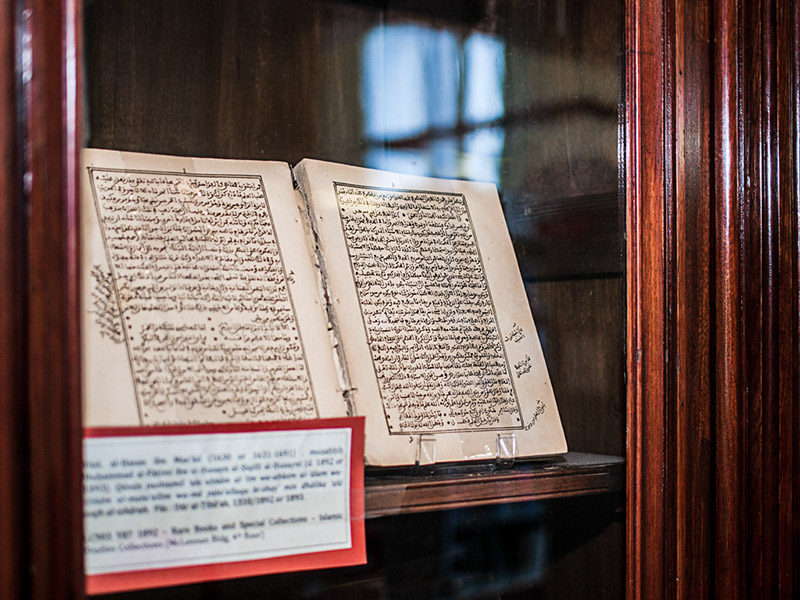

- lithography was very versatile, offering a wide range of possibilities in the production of designs and maps, and an extremely precise reproduction of the outlines of Arabic calligraphy avoiding any rupture with the manuscript tradition

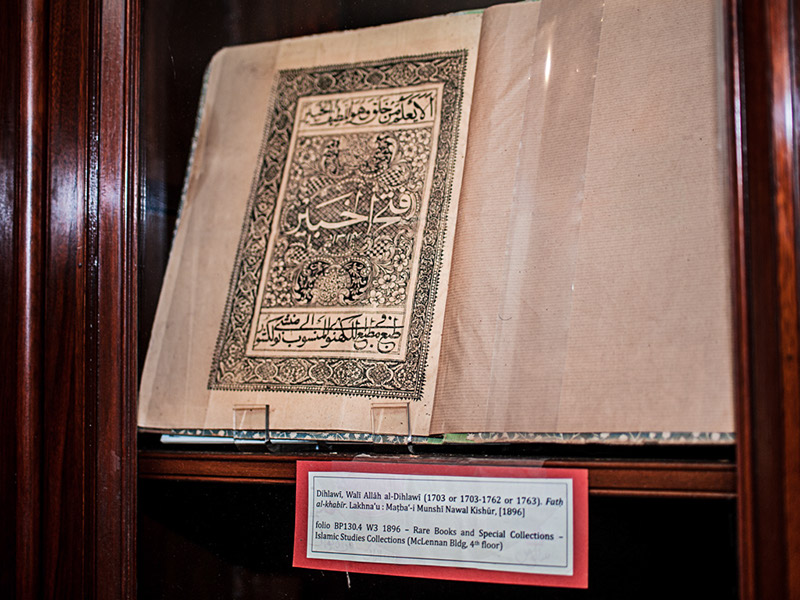

- lithographed books were visually very similar to manuscripts, in the textual, graphic, and artistic layout, avoiding any disruption of reading habits

- printing by lithography was not seen as a threat by the powerful guild of copyists since it required the skills of trained calligraphers.

1Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed largely of skeletal fragments of marine organisms

such as coral or foraminifera.

2Arabic gum, also known as Mastic, is a resin obtained from the mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus)

3Shaw, G. W. (1989). "Maṭbaʿa". In P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel (eds.),

Encyclopaedia of Islam, second Edition. Leiden : E. J. Brill. pp. 794-807

4The invention of printing by movable types of metal alloy is commonly attributed to Johann Gensfleisch,

better known as Gutenberg (mid-fifteenth century).

Although expensive and difficult to operate, this printing technique revolutionized the book production in Europe.

5Messick, Brinkley (2013). On the Question of Lithography.

In Geoffrey Roper (ed.), The history of the book in the Middle East.Farnham, Surrey ; Burlington, VT : Ashgate. p.302

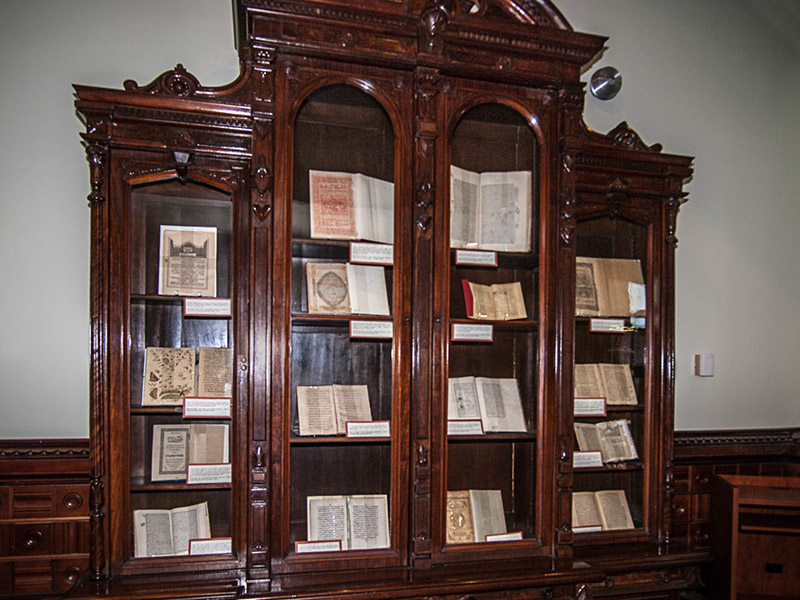

Although modest, McGill Islamic lithographs collection — consisting of approximately 750 volumes, dated from the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century — is interesting for several reasons. First, the books are in four different languages:

- 264 in Arabic

- 253 in Persian

- 196 in Urdu

- 36 in Ottoman Turkish (Turkish written in Arabic script)

- Matba' al-Munshi Nawal Kishur (Lucknow, India)

- Matba'a-I 'Uthmaniyah (al-Matba'ah al-'Uthmaniyah) (Istanbul, Turkey)

- al-Matba'ah al-Jadidah (Fez, Morocco)

- Dar Tiba'at Ibrahim al-Tabrizi (Tabriz, Iran)

- Matba'-i Nizami (al-Matba' al-Nizami, al-Matba'ah al-Nizamiyah) (Cawnpore, India)

- al-Matba'ah al-Baruniyah (Cairo, Egypt).

This digital collection aims to give full access to McGill Islamic lithographs collection: it is a continually updated resource. It can be browsed either by country of publication or language.

6Gacek, Adam (1996). Arabic lithographed books in the Islamic Studies Library, McGill University : descriptive catalogue. Montreal : McGill University Libraries. p. 2