© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada /

© National Gallery of Canada / |

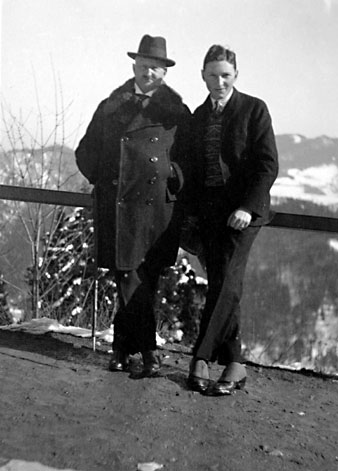

The History of Max Stern's Library Dr. Max Stern (1904-1987) was an art collector and art dealer, the owner of the Dominion Gallery in Montreal, and a generous donor of works of art to public collections. His library was a working library. The largest and most valuable part of the collection, including rare editions, was acquired before he came to Canada in 1941. The comprehensive book collection he amassed as a young man formed the basis of his knowledge and expertise. After Stern moved to Canada his library evolved even further from an art historian’s library to that of an art collector and dealer. Max Stern began collecting books at an early age. He bought and was given books when he was a student of art history from 1923 to 1928, studying for five semesters in Cologne, Berlin and Vienna, and graduating with a Dr. Phil. from Bonn University in 1928. Oddly enough, his collection includes few books by his professors, most of them still major names in German art history today. In his first semester he studied Baroque art at the University of Cologne under A.E. Brinckmann (1881-1958); he owned four books by him, one on Baroque sculpture. In Berlin one of Stern’s professors was Adolf Goldschmidt, Dean of the History of Art at Berlin University (1863-1944); the 1923 Festschrift for Goldschmidt’s 60th birthday is in Stern’s collection. Another teacher was Edmund Hildebrandt (1872-1939), whose books on Watteau, 18th-century French art and Leonardo did not enter Stern’s collection until later. In Vienna, in the winter semester 1923/24, he studied under Julius von Schlosser (1866-1938) and Josef Strzygowski, Director of the Institute of Art History (1862-1941). In view of the importance of these scholars, it is surprising that the Stern collection presently contains only one book by Strzygowski. At Bonn University Stern studied under Paul Clemen (1866-1947), who became his dissertation supervisor. Stern owned a number of his books, though he did not acquire many of them until later. Other professors and mentors in Bonn and Düsseldorf were Karl Koetschau (1868-1949), Richard Klapheck, Paul Horn, and Walter Cohen (1880-1942), art historians in both academic and museum circles. Most of his teachers in Bonn were friends of his father’s and remained close and important contacts. Each is represented by several titles in Stern’s collection, though many of these were not acquired until after his student days. One curiosity dating back to Stern’s student days is the two-volume set of an art history textbook (Goeler von Ravensburg, Grundriss der Kunstgeschichte: Handbuch für Studierende [Outline of Art History: a Handbook for Students] ed. by Max Schmid-Burgk, 1923) that he had rebound with interleaved graph paper making four volumes, so that he could take notes on lectures and his readings beside the corresponding pages in the text. These notes, handwritten in ink, in Old German script, are accompanied by rough sketches of the works of art and architecture. Another basic text of his at university would have been Heinrich Wölfflin’s Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe (Principles of Art History), of which he had two editions. As Stern recalled in his tape-recorded memoirs, preserved in the Dominion Gallery archives at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, he was more interested in developing his connoisseurship than in scholarly art history or theory. This would explain the range of artists and the abundance of illustrated material in his collection as well as the emphasis on monographs and on exhibition and museum catalogues. These interests are reflected in his library throughout his life, even when he changed his focus from Old Masters to contemporary art. Max Stern was exposed to art and the art business at his father’s art gallery, Galerie Julius Stern in Düsseldorf, where he began gaining practical experience in his youth. His collection features many art auction and sales catalogues (often with handwritten entries), works on expertise and art fraud, art prices, forgery and related topics. Most of the older volumes had belonged to his father. Stern’s doctoral dissertation is a monograph on a 19th-century German academic painter, Johann Peter Langer. Relying on his connoisseur’s eye as well as graphology, not to mention assertiveness in knocking on doors of everyone from curators to aristocratic collectors, he tracked down clues and assembled hundreds of lost works in only three years. In his copy of Richard Klapheck, Geschichte der Kunstakademie zu Düsseldorf (History of the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, 1919) he underlined every passage in pencil that concerns Langer. Found in this book were carbon copies of two letters he wrote requesting information on Langer and the Düsseldorf academy when he started his research in 1925. Museum and exhibition catalogues trace his travels for study and research in European cities: Munich (when he was a student in 1921-25 and doing doctoral research in 1927), Nürnberg (1924-25), Vienna (1923, 1926), Budapest (when he was preparing to start his dissertation in 1924), Paris and Rome in the mid-1920s when he was a student. Others are from Amsterdam and other Dutch cities and were acquired in the 1930s when he was preparing to leave Germany. Catalogues of American collections date from his trip to the USA from London in the spring of 1939, often noting the names and addresses of directors, curators and other important contacts. As are his books, these catalogues are inscribed with his name. If the place and the date are also included, it means he had been there himself. A few books also include the date of acquisition and the name of the bookstore. In 1934 upon the death of his father Julius, Max Stern became the owner of his father’s art gallery. Julius Stern (1867-1934) had been a textile manufacturer and an art collector, who opened an art gallery in Düsseldorf after Max was born. He started to hold auctions at his gallery in the 1920s. Max inherited his father’s books, for in Max’s memoirs he said that, when he came to Canada, his collection consisted of the libraries of his father and of Professor Koetschau. Both collections emphasize the art of the Rhineland, particularly Düsseldorf. Julius Stern wrote his name in some of his books, many of which are inscribed with dedications from his art historian friends at universities and museums. About fifty books have the stamp of his gallery in them. Four contain the ex libris of Hanns Schreiner. Max later inscribed both books and catalogues inherited from Julius’s collection in pencil on the flyleaf with Dr. Max Stern.

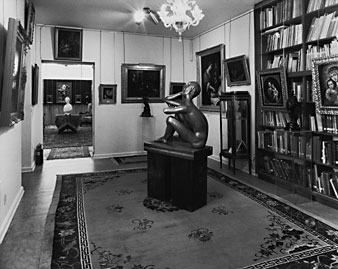

Koetschau’s books and shelves are also mentioned in a letter from a friend who helped Stern organize his exile in 1937. That letter also mentions two lists of books and catalogues. Perhaps this refers to the undated typed lists, one of books, one of auction catalogues and one of exhibition catalogues (now in the Dominion Gallery archives at the National Gallery). The list of the books must have been made before they were packed in 1937; additional handwritten entries are all dated 1937. It lists the books according to subject, using a classification system that probably originated with Stern. Most of the books from Koetschau’s library have one of two bookplates in them. One is by the painter Ernst Liebermann (1869-1960), the other by the painter and graphic artist Adolf Uzarski (1885-1970). Many of Koetschau’s books are also stamped with a round ownership stamp that contains a handwritten accession number, and some are signed. Stern probably did not take over all of Koetschau’s collection because books in Koetschau’s subject specialties such as arms and armour or Goethe, which he must have owned too, are not represented in Stern’s library. Koetschau’s collection reflects a museum director’s and art historian’s interests. He was not as scholarly or important art historian as, for example, his friend Paul Clemen, though he did publish prolifically, mostly articles. His main focus was on the art of the Rhineland; other interests include late medieval art and northern Renaissance. Wherever he worked, he reorganized collections and introduced more modern ways of museum presentation. He had many museum catalogues. Many books contain dedication inscriptions by the authors, as do the many off-prints from journals. Some are review copies and include his handwritten comments and corrections. There are not many books on art theory or the history of ideas. This suited Max Stern’s tastes and needs. His library was meant to serve his work, as did his father’s. The majority of the books are monographs, providing the art dealer with pictures and data he would need for expertise. With conditions in Nazi Germany becoming increasingly dangerous for Jews and business declining, Max Stern decided to leave Germany. In 1937, he closed Galerie Julius Stern, sold the house at Königsallee 23-25 that had been the family home and the gallery premises (the Nazis had already changed the name of the street to Albert Leo Schlageter). He sold the gallery’s collection at auction, packed his belongings and put them into storage, and moved to London in December of the same year. His books arrived in London in January 1939. They remained in storage in a Barclay’s Bank safe in London. After a period of internment as an enemy alien in England, he moved to Canada in 1941, where he was also interned. In 1946, after he had married Iris Westerberg in Montreal, he went back to England to arrange his affairs: “I could now bring my paintings from England to Canada, as well as my library” (as he said in his memoirs). They were first stored at Morgan’s in Montreal. In Canada, Stern’s library developed as an art dealer’s library rather than that of an art historian. With few exceptions, e.g. a book by Held on Rubens in 1954, he seems to have stopped buying scholarly books on art history or acquiring older publications. He was also acquiring fewer books (of ca 1,500 titles, 794 were bought before 1937, 35 during the war, 416 after 1946). His new book acquisitions reflect the change in what he was buying and selling at his gallery. Old Masters were harder to deal in than in Europe (though he continued sell some and to provide expertise) and hence Stern’s emphasis shifted to contemporary and Canadian art. He was one of the first Canadian gallery owners to make exclusive contracts with artists, and of course his library includes books and/or catalogues on every artist he represented. He was influential in the lifting of Canada’s import duty on sculpture in 1956, and as soon as he was able to bring sculpture into the country, he focused on that medium, which he saw as the art form of the future. His new focus is reflected in his many books and catalogues on contemporary European and Canadian sculptors, as well as on Rodin, of whose works he held a major exhibit in 1967. As in his father’s and his own book collection in Germany, the range of artists represented continued to be impressively broad and to reflect the business of the gallery. Stern knew what great art was and collected it himself, but it was not only the best art that sold well. Unlike his father, whose friendships were with art historians in academic and museum circles, Max Stern was closer to his artists. This is partly because Julius sold Old Masters’ and Max sold mainly contemporary artists’ work. His long-term personal relationships with artists whose work he collected and/or sold are reflected in the warm inscriptions in books and catalogues presented to him and his wife. The gifts are sometimes signed with “love” and frequently acknowledge his support. The Portuguese-Canadian painter Martha Teles, for example, whom Stern recommended for a Canada Council grant and who painted a portrait of Stern in 1981, sent him the catalogue of an exhibition (for which Stern had lent works) and a monograph on herself after she returned to Portugal. This is only one case illustrating the role Max Stern played as a catalyst in the Montreal art scene for over 50 years, spreading awareness of contemporary artists, whether they were major or minor in stature, local or international in reputation. The Dominion Gallery stamp was added to the books after Stern moved the gallery to the building he bought on Sherbrooke Street in 1950, where he worked and lived until the end of his life. Max Stern’s library meant a lot to him. The fact that he bequeathed it to three university libraries shows how he appreciated its value. When his books arrived in London in 1939 he expressed relief that he had managed to save his library and get it out of Germany. He always kept his older books with him, even when he was no longer using them as a part of his working library. In 1950 after renovations to the newly acquired Dominion Gallery building, Stern described the new rooms in a letter. The library was to be in two rooms on the second floor (the architect’s floor plan shows the library in one room at the back). After the second renovation, in 1959, he wrote that the library was not in order yet and that he may hire a young woman to organize it. He also mentioned he had ordered book cases with glass doors that could be locked, so that books could be safeguarded as the gallery did not have the staff to watch every room. In fact, the books were not in one room but scattered throughout the gallery building and in his home upstairs on the top floor. There were also bookshelves in his office. Max Stern bequeathed his library to McGill University and Concordia University in Montreal and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. At McGill the Max Stern Collection of both Montreal universities is housed in the Rare Books and Special Collections Division of the McGill University Libraries on the fourth floor of McLennan Library.

|