Woman is a citizen by right, if not in fact, and, as such, she must involve herself in public life, in social life.

– Pauline Roland (1851, cited in Foley, 2004, 128).

Liberty was personified as a woman, and yet women had very few liberties in nineteenth-century France. They were considered minors, subordinate to their husbands, and lacked economic emancipation. As Claire Moses has noted, the 1804 Napoleonic civic code enshrined sexual difference (1984). With the political unrest following the 1848 Revolution, however, the women’s movement at last gained momentum across Europe, including France. Women formed organizations and created newspapers in order to fight for equal rights, including the right to participate in public affairs, to be economically independent, and, of course, to vote. Notable figures included Eugénie Niboyet, Jenny d’Héricourt, and Jeanne Deroin (who even ran for office). Although women’s mobilization was initially short-lived, crushed like many other social organizations under the restrictions of public assembly, the groundwork for social change had been laid.

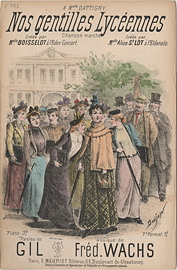

The 1860s sparked another surge in the women’s movement with Louise Michel, Paule Mink, and Hubertine Auclert (the first self-proclaimed féministe), to name only a few of the women who challenged the legal and social status quo. Although socialist feminists and bourgeois feminists had diverging priorities, by the 1880s and 1890s, the women’s movement had made some headway: women could divorce, have a bank account, and join certain professions. In 1881, France established secondary schools for girls, and by the end of the century, women had much greater access to education. Suffrage, however, was left aside; French women would not gain the vote until 1944.

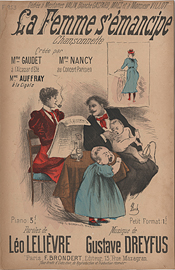

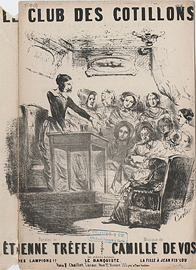

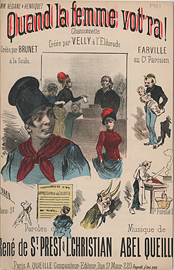

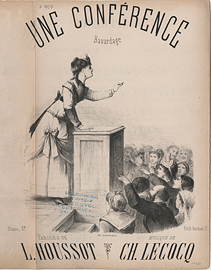

Women’s activities as well as society’s responses to their demands for change were addressed, ridiculed, and challenged on the café-concert stage. Popular song documented the social anxieties surrounding the question des femmes (women’s question), with pieces that simultaneously satirize and lament the possible reversal of responsibilities. The press also propagated an image of the nouvelle femme as “educated, sport-playing, cigar-smoking, marriage-hating” (cited in Offen, 2000, 189), a representation echoed in the texts and on the covers of many café-concert chansons.